Questions about truth and falsity saturate our existence as humans. While we may not always know what is true, we have intuitive ideas of what it would mean for something to be true and work very hard to get “closer” to it. We regularly make claims about what is true seemingly with little to no difficulty. Yet we find ourselves in a constant battle with falsehoods. Our work, our love lives, and even our most cherished recreational times are laden with discovering truth over falsehood. Is that theory true? Is my spouse lying to me? Did the goalie actually deserve that yellow card? So while truth may be an idea we use readily, getting to the truth is surprisingly difficult. Ironically, even definitions of truth that philosophers have developed fall prey to the question, “Are they true?” Still, a definition is as good a place to start as any so here’s one: truth is a statement about the way the world actually is. Let’s explore how good that definition is!

Elusive Truth

Suppose you examine an apple and determine that it’s red, sweet, smooth and crunchy. You might claim this is what the apple is. Put another way, you’ve made truth claims about the apple and seemingly made statements about real properties of the apple. But immediate problems arise. Let’s suppose your friend is color blind (this is unknown to you or her) and when she looks at the apple, she says that the apple is a dull greenish color. She also makes a truth claim about the color of the apple but it’s different than your truth claim. What color is the apple?

Well, you might respond, that’s an easy problem to solve. It’s actually red because we’ve stipulated that your friend has an anomaly in her truth-gathering equipment (vision) and even though we may not know she has it, the fact that she does means her perception of reality is incorrect. But now let’s suppose everyone is color blind and we all see “red” apples as green? Now no one has access to the “real” color of the apple. Again, the response might be that that this is a knowledge problem, not a truth problem. The apple really is red but we all believe it’s green. But notice that the truth of the apple’s color has little role to play in what we believe. No one knows what the truth is and so it plays no role in our epistemology.

The challenge is that our view of truth is very closely tied to our perspective on what is true. This means that in the end, we may be able to come up with a reasonable definition of truth, but if we decide that no one can get to what is true (that is, know truth), what good is the definition? Even more problematic is that our perspective will even influence our ability to come up with a definition! These are no small concerns and we’ll explore some responses below.

Some Preliminaries

Epistemologists (people who study truth, belief and knowledge) use the following concepts as the framework for their study of truth.

Propositions. A common technical definition of a proposition (credited to Peter van Inwagen) is “a non-linguistic bearer of truth value.” A proposition is a representation of the world or a way the world could possibly be and propositions are either true or false. Propositions are different than sentences. Sentences are symbolic, linguistic representations of propositions. Okay, that’s all very technical. What does it mean?

Let’s take the sentence, “The moon has craters.” This is an English sentence that supposedly states some fact about the world or reality. Because it’s in English, we say it’s “linguistic” or language-based. Specifically, we can describe the sentence’s properties as having four words and 17 letters, it’s in the English language written in 11 point font and it’s black. I could write the same sentence like this:

The moon has craters.

This one still has the same number of words and letters and it’s in English. But it is in 18 point font and is written in blue. Now let’s take this sentence, “La luna tiene cráteres.” This sentence has four words but 19 letters. It’s written in 11 point font and is black but it’s Spanish. What do all three sentences have in common? Well, they all express the same idea or meaning and we could say the same “truth.” We could express the same idea in Swahili, semaphore, Morse code, or any other symbolic system that conveys meaning.

Notice that the symbols themselves are neither true nor false. The meaning the sentences represent is either true or false. This “other thing” the sentences represent are propositions. Put another way, the common property true of all sentences that express the same truth is what philosophers call the propositional content of the sentences or “the proposition.” Now we can better understand the idea behind “non-linguistic bearer of truth value.” Propositions are non-linguistic because they aren’t written or spoken in a language. They bear truth because they are the things that are true or false. This is what allows them to be expressed or “exemplified” in a variety of different symbolic systems like language-based sentences. When it comes to understanding truth, many philosophers believe propositions are at the center.

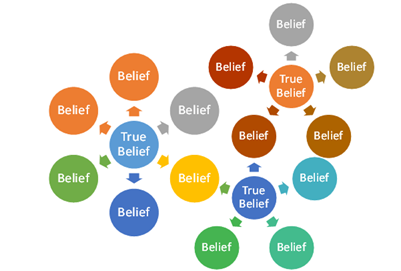

Belief. Beliefs are things (at least) people have. They don’t exist outside the mind. Some philosophers say beliefs are “dispositional.” That is, they incline a person to behave in a way as if the thing they believe is true. So a belief, simply, is a proposition that a person accepts as representing the way the world actually is. Beliefs can be about false propositions and thus be “wrong” because the person accepts them as true. This is a critical distinction. While a proposition has to be true or false, beliefs can be about true or false propositions even though a person always accepts them as true.

Some philosophers attempt to define truth “mind-independently.” That means, they want to come up with a definition that doesn’t depend on whether humans can actually believe or know what is true. Truth is viewed as independent of our minds and they seek a definition of it that captures this. Other philosophers have developed theories that keep people at the center. That is, truth and belief are considered together and are inseparable. I will try to make the relevance of the “epistemic” vs. “independent” views of truth relevant below.

Knowledge. Knowledge is belief in a true proposition that a person is justified in holding as true. The conditions under which a person is justified is somewhat complex and there are many theories about when the conditions are met. Theories of knowledge attempt to describe when a person is in a “right” cognitive relationship with true propositions. I describe some theories of knowledge and some of the challenges in understanding when a person knows in an article for Philosophy News called “What is Knowledge?“

Common Definitions

The Coherence View of Truth

The main idea behind this view is that a belief is true if it “coheres” or is consistent with other things a person believes. For example, a fact a person believes, say “grass is green” is true if that belief is consistent with other things the person believes like the definition of green and whether grass exists and the like. It also depends on the interpretation of the main terms in those other beliefs. Suppose you’ve always lived in a region covered with snow and never saw grass or formed beliefs about this strange plant life. The claim “grass is green” would not cohere with other beliefs because you have no beliefs that include the concept “grass.” The claim, “grass is green” would be nonsense because it contains a nonsensical term. You’ve never formed a belief about grass so there’s nothing for this new belief to cohere with.

As you can see, coherence theories typically are described in terms of beliefs. This puts coherence theories in the “epistemic” view of truth. This is because, coherence theorists claim, we can only ground a given belief on other things we believe. We cannot “stand outside” our own belief system to compare our beliefs with the actual world. If I believe Booth shot Lincoln, I can only determine if that belief is truth based on other things I believe like “Wikipedia provides accurate information” or “My professor knows history and communicates it well” or “Uncle John sure was a scoundrel.” These are other beliefs and serve as a basis for my original belief.

Thus truth is essentially epistemic since any other model requires a type of access to the “real world” we simply can’t have. As philosopher Donald Davidson describes the situation, “If coherence is a test of truth, there is a direct connection with epistemology, for we have reason to believe many of our beliefs cohere with many others, and in that case we have reason to believe many of our beliefs are true.” (Davidson, 2000)

The Correspondence Theory of Truth

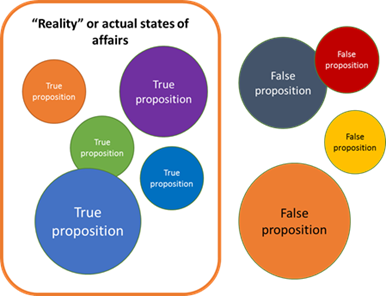

Arguably the more widely-held view of truth, philosophers who argue for the correspondence theory hold that there is a world external to our beliefs that is somehow accessible to the human mind. Specifically, correspondence theorists hold that there are a set of “truth-bearing” representations (propositions) about the world that align to or correspond with reality. When a proposition aligns to the way the world actually is, the proposition is said to be true. Truth, on this view, is that correspondence relation.

Take this proposition: “The Seattle Seahawks won Super Bowl 48 in 2014.” The proposition is true if in fact the Seahawks did win super Bowl 48 in 2014 (they did) and false if they didn’t.

The correspondence theory only lays out the condition for truth in terms of propositions and the way the world actually is. This definition does not involve beliefs that people have. Propositions are true or false regardless of whether anyone believes them. Just think of a proposition as a way the world possibly could be: “The Seahawks won Super Bowl 48” or “The Seahawks lost Super Bowl 48” — both propositions possibly are true. True propositions are those that correspond to what actually happened.

Postmodernism

Postmodern thought covers a wide theoretical area but informs modern epistemology particularly when it comes to truth. In simple terms, postmodernists describe truth not as a relationship outside of the human mind that we can align belief to but as a product of belief. We never access reality because we can never get outside our own beliefs to do so. Our beliefs function as filters that keep reality (if such a thing exists) beyond us. Since we can never access reality, it does no good to describe knowledge or truth in terms of reality because there’s nothing we can actually say about reality that’s meaningful. Truth then is constructed by what we perceive and ultimately believe.

Immanuel Kant

I’m inclined to earmark the foundation of postmodern thought with the work of Immanuel Kant, specifically with his work The Critique of Pure Reason. In my view, Kant was at the gateway of postmodern thought. He wasn’t a postmodernist himself but provided the framework for what later developed.

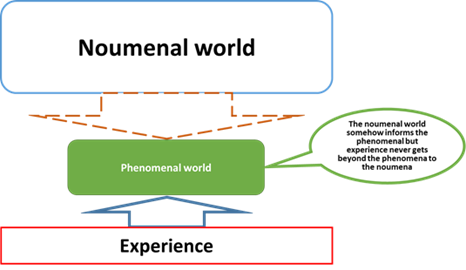

Kant makes a foundational distinction between the “objects” of subjective experience and the “objects” of “reality.” He labels the former phenomena and that latter noumena. The noumena for Kant are things in themselves (ding an sich). These exist outside of and separate from the mind. These are what we might call “reality” or actual states of affairs similar to what we saw in the correspondence theory above. But for Kant, the noumena are entirely unknowable in and of themselves. However, the noumena give rise to the phenomena or are the occasion by which we come to know the phenomena.

The phenomena make up the world we know, the world “for us” (für uns). This is the world of rocks, trees, books, tables, and any other objects we access through the five senses. This is the world of our experience. This world, however, does not exist apart from our experience. It is essentially experiential. Kant expressed this idea as follows: the world as we know it is “phenomenally real but transcendentally ideal.” That is, objects that we believe exist in the world are a “real” part of our subjective experience but they do not exist apart from that subjective experience and don’t transcend the beliefs we have. The noumena are “transcendentally real” or they exist in and of themselves but are never experienced directly or even indirectly.

The noumena are given form and shape by what Kant described as categories of the mind and this ‘ordering’ gives rise to phenomenal objects. This is where it relates to truth: phenomenal objects are not analogues, copies, representations or any such thing of the noumena. The noumena gives rise to the phenomena but in no way resembles them. Scholars have spent countless hours trying to understand Kant on this point since it seems like the mind interacts with the noumena in some way. But Kant does seem to be clear that the mind never experiences the noumena directly and the phenomena in no way represents the noumena.

We can now see the beginnings of postmodern thought. If we understand the noumena as “reality” and the phenomena as the world we experience, we can see that we never get past our experience to reality itself. It’s not like a photograph which represents a person and by seeing the photograph we can have some understanding of what the “real person” actually looks like. Rather (to use an admittedly clumsy example) it’s like being in love. We can readily have the experience and we know the brain is involved but we have no idea how it works. By experiencing the euphoria of being in love, we learn nothing about how the brain works.

On this view then, what is truth? Abstractly we might say truth is found in the noumena since that’s reality. But postmodernists have taken Kant’s idea further and argued that since we can’t say anything about the noumena, why bother with them at all? Kant didn’t provided a good reason to believe the noumena exist but seems to have asserted their existence because, after all, something was needed to give rise to the phenomena. Postmodernists just get rid of this extra baggage and focus solely on what we experience.

Perspective and Truth

Further, everyone’s experience of the world is a bit different–we all have different life experiences, background beliefs, personalities and dispositions, and even genetics that shape our view of the world. This makes it impossible, say the postmodernists, to declare an “absolute truth” about much of anything since our view of the world is a product of our individual perspective. Some say that our worldview makes up a set of lenses or a filter through which we interpret everything and we can’t remove those lenses. Interpretation and perspective are key ideas in postmodern thought and are contrasted with “simple seeing” or a purely objective view of reality. Postmodernists think simple seeing is impossible.

We can see some similarities here to the coherence theory of truth with its web of interconnected and mutually supported beliefs. On the coherence theory, coherence among beliefs gives us reason to hold that what we believe corresponds to some external reality. In postmodernism there is nothing for our beliefs to correspond to or if there is, our beliefs never get beyond the limits of our minds to enable us to make any claims about that reality.

Community Agreement

Postmodernism differs from radical subjectivism (truth is centered only in what an individual experiences) by allowing that there might be “community agreement” for some truth claims. The idea is that two or more people may be able to agree on a particular truth claim and form a shared agreement. To be clear, the perspective is not true because they agree it maps or corresponds to reality. But since the members of the group all agree that a given proposition or argument works in some practical way, or has explanatory power (seems to explain some particular thing), or has strong intuitive force for them, they can use this shared agreement to form a knowledge community.

When you think about it, this is how things tend to work. A scientist discovers something she takes to be true and writes a paper explaining why she thinks it’s true. Other scientists read her paper, run their own experiments and either validate her claims or are unable to invalidate her claims. These scientists then declare the theory “valid” or “significant” or give it some other stamp of approval. In most cases, this does not mean the theory is immune from falsification or to being disproved–it’s not absolute. It just means that the majority of the scientific community that have studied the theory agree that it’s true given what they currently understand. This shared agreement creates a communal “truth” for those scientists. This is what led Richard Rorty to state the oft-quoted phrase, “Truth is what my colleagues will let me get away with.”

What is Truth?

So we have some theories but it seems we’re no closer to answering our question. Which theory is true? Kant surely was on to something when he claimed that we have to start with our beliefs if for no other reason than that it seems impossible to deny. Any “reality” statement recast as a belief statement seems to be an exercise that adds specificity. But the reverse isn’t truth. For example, the claim, “Harvard’s library contains a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary” can readily be recast as “I believe Harvard’s library contains a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary” we naturally take this second statement as adding clarity to what we meant by the first. But if we restate, “I believe Harvard’s library contains a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary” as “Harvard’s library contains a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary” we lose the meaning of the first statement. We can see this if we add the additional phrase, “but I don’t believe it.” The “reality” statement is supposed to make a claim about the Harvard library but without the belief qualifier, we have no way to access its truth condition. In other words, the only way to get at the world is through our minds and our minds are filled with beliefs and only beliefs. If you object and claim that minds can be filled with true propositions, isn’t that something you believe?

So the question then becomes, do our beliefs correspond to the way the world actually is—do we access the noumena—or do we filter everything such that our beliefs do not correspond

Practical Concerns

Philosophers are supposed to love wisdom and wisdom is more oriented towards the practical than the theoretical. This article has been largely about a theoretical view of truth so how do we apply it? Most people don’t spend a whole lot of time thinking about what truth is but tend to get by in the world without that understanding. That’s probably because the world seems to impose itself on us rather than being subject to some theory we might come up with about how it has to operate. We all need food, water and shelter, meaning, friendship, and some purpose that compels us to get out of bed in the morning. This is a kind of practical truth that is not subject to the fluidity of philosophical theory.

Even so, we all contend with truth claims on a daily basis. We have to make decisions about what matters. Maybe you’re deeply concerned about politics and what politicians are claiming or what policy should be supported or overturned. Perhaps you care about which athlete should be traded or whether you should eat meat or support the goods produced by a large corporation. You may want to know if God exists and if so, which one. You probably care what your friends or loved ones are saying and whether you can count on them or invest in their relationship. In each of these cases, you will apply a theory of truth whether you realize it or not and so a little reflection on what you think about truth will be important.

Your view of truth will impact how you show up at work and impacts the decisions you make about how to raise your children or deal with a conflict. For example, suppose you’re faced with a complex question at work about something you’re responsible for. You need to decide whether to ship a product or do more testing. If you’re a postmodernist, your worldview may cause you to be more tentative about the conclusions you’re drawing about the product’s readiness because you understand that your interpretation of the facts you have about the product may be clouded by your own background beliefs. Because of this, you may seek more input or seek more consensus before you move forward. You may find yourself silently scoffing at your boss who makes absolute decisions about the “right” way to move forward because you believe there is no “right” way to do much of anything. There’s just each person’s interpretation of what is right and whoever has the loudest voice or exerts the most force wins.

An engineer may disagree here. She may argue, as an example, that there is a “right” way to build an airplane and a lot of wrong ways and years of aviation history documents both. Here is an instance where the world imposes itself on us: airplanes built with wings and that follow specific rules of aerodynamics fly and machines that don’t follow those “laws” don’t. Further most of us would rather fly in airplanes built by engineers that have more of a correspondence view of truth. We want to believe that the engineers that built the plane we’re in understand aerodynamics and built a plane that corresponds with the propositions that make up the laws of aerodynamics.

Your view of truth matters. You may be a correspondence theorist when it comes to airplanes but a postmodernist when it comes to ethics or politics. But why hold different views of truth for different aspects of your life? This is where a theory comes in. As you reflect on the problems posed by airplanes and ethics, the readiness of your product to be delivered to consumers and the readiness of your child to be loosed upon the world, about what makes you happy and about your responsibility to your fellow man, you will develop a theory of truth that will help you navigate these situations with more clarity and consistency.

Bibliography

Ackerman, D. F. (1976, December). Plantinga, Proper Names and Propositions. Philosophical Studies, 30, 409-412.

Barrett, W. (1962). Irrational Man. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books.

Brown, C. (1986). What Is a Belief State? Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 10, 357-78.

Brown, C. (1992). Direct and Indirect Belief. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 52, 289-316.

Chisholm, R. (1957). Percieving: A Philosophical Study. Ithaca: Cornell University.

Chisholm, R. M. (1989). Theory of Knowledge (3 ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Davidson, D. (2000). A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge. In S. Bernecker, & F. Dretske (Eds.), Knowledge: Readings in Contemporary Epistemology (pp. 413-428). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dennett, D. C. (1998, August 13). Postmodernism and Truth. Retrieved December 26, 2014, from Tufts: http://ase.tufts.edu/cogstud/dennett/papers/postmod.tru.htm

Frankfurt, H. (2005). On Bullshit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Frankfurt, H. (2006). On Truth. New York: Knopf.

Gettier, E. (2000). Is Justified True Belief Knowledge. In S. Bernecker, & F. Dretske (Eds.), Knowledge: Readings in Contemporary Epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

James, W. (1907). Pragmatism. Amazon Digital Services, Inc.

Kripke, S. (1980). Naming and Necessity. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press.

Strawson, P. F. (1950). On Referring. Mind, 59(235), 320-344.

Williams, B. (2004). Truth and Truthfulness. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press